#18. How were exam results determined? Was it fair? What's going to happen?

TL;DR — in a complicated manner; no; uhhh...

Hi all,

This one is going to go into a lot of technical detail with regards to the calculation of grades in the absence of exams! I’m very interested in it. If you’re not, that’s OK.

I was 16. It was the day before one of my GCSE Biology exams, and we had an end-of-the-day biology revision session with the teacher. We did a mock exam with a practice paper and then went through it together with the teacher explaining things on the overhead projector(!).

We spent a lot of time, perhaps a half an hour in total, on the last question. It was a strange one — while the rest had been about standard biology things like osmosis or whatever, this one had involved doing some mathematical reasoning to determine the water resistance of crude fish-shaped object. It was worth a lot of marks, and practically all of us had got stumped. It almost didn't seem to belong to that paper at all and was nothing like anything we'd covered.

The next day got up on time, queued up, chatting mildly, got into the exam hall and waited for the signal to turn over our papers. No one really likes exams, but I find them particularly challenging — the time pressure gets to me and I start spiralling. Also I handwrite quite slowly and not very neatly — my English teacher once told me this would hold me back all of my life, but fortunately it only held me back at school.

I worked through the questions, which were all fine, and then turned over to the final page.

It was exactly the same question we had spent so long studying with our teachers the day before. Exactly.

When we left the exam hall we were all discussing it. Did you see that last question? Don't say anything! I slyly mentioned it to my teacher and she said she wasn't sure what I could be referring to.

Last week A Level results were released in England, and similarly with Highers in Scotland. Next week GCSE results are due to be released. These have been calculated not based on exams, and only obliquely on learning. They are based on the performance of schools and the opinion of teachers of their students, fed into an algorithm which spits out grades. Many people are unhappy, because they have not received the grades that they thought they would get, or that represent their potential.

Here is one example of the complexity involved. For the past four years, Ramadan — a period that for nearly all Muslims involves fasting from food and water during daylight hours — has coincided with the exams period. Schools have become concerned that this depresses the performance of their Muslim students, putting in place special guidance to minimise the impact. This year however, Ramadan and the exams period do not coincide. How do you take this into account?

It becomes increasingly obvious that what Ofqual have been asked to do amounts to a wholesale simulation of 'reality as if COVID19 had not happened'.

So how have they done it?

How have they done it!

I'm going to present a simplified example. We'll imagine a grade system of just A, B, & C. We'll focus in on one school — let's call it Cova Academy, and one subject — English A Level — with 3 classes of 8 students each (= 24 students).

To do this we generate

Step 1: Get some Grade Distributions

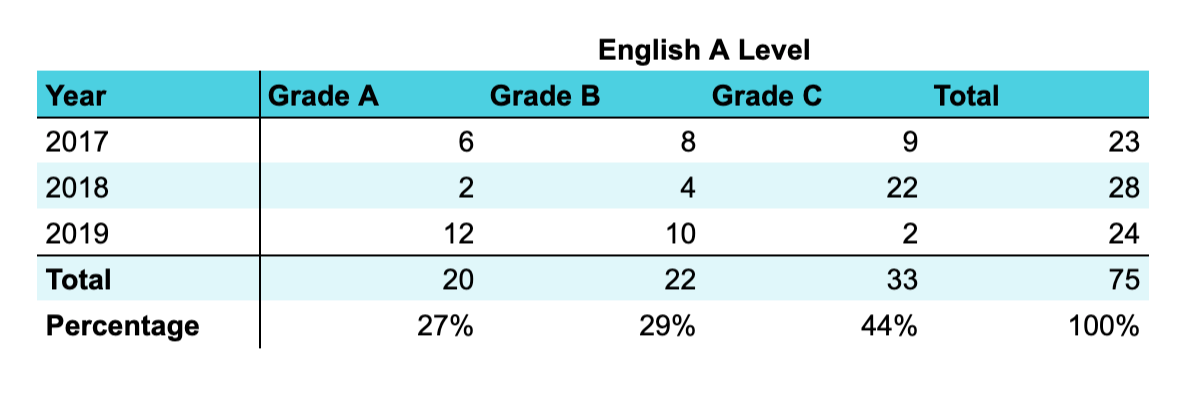

Each year the English students at Cova get some grades — e.g. 6 get As, 8 get Bs, 9 get Cs. We'll call that the Grade Distribution. This year is no different.

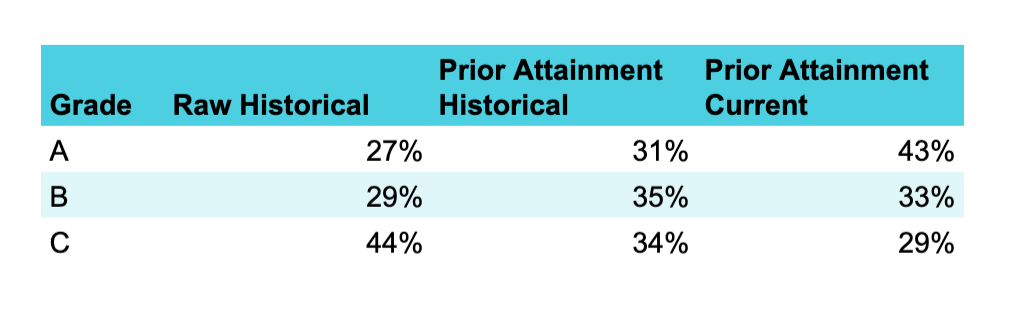

This step is about creating 3 different grade distributions, which we'll later measure off against each other.

Grade Distribution Based on Past Grade Distributions

The idea here is to work out what grades the English students at Cova typically get. To do this, we look at the last 3 years of student data, like so:

And so you get, over the past 3 years:

27% got As

29% got Bs

44% got Cs

This is our historical grade distribution.

Now there are a few bits more analysis to do, but it's useful to jump ahead so you can see where this is going. At the end of this process we're going to give Cova Academy a 'bag of grades' to allocate amongst its students. Ofqual don't do this just yet, but let's look at what grades Cova would get to allocate based just on the above:

AAAAAABBBBBBBCCCCCCCCCCC

But not just yet.

Grade Distribution Based on Students Like Cova's

The idea here is that to work out what the sort of students of the ability Cova has had in the past typically get.

To do this, we take a big database of recent students who have done both GCSEs and A Levels across the country.

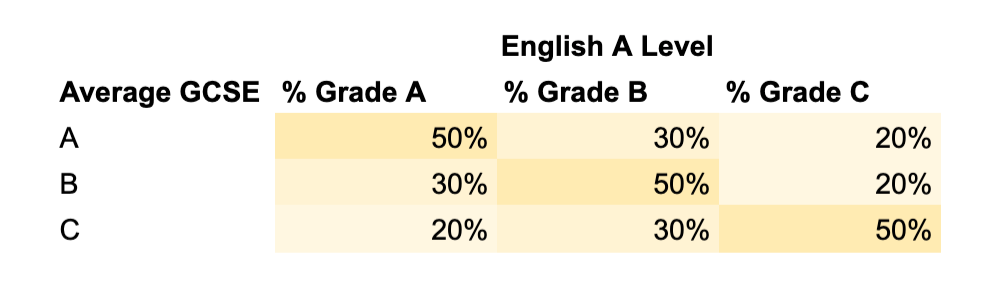

We work out for each student what their average GCSE result was (across all subjects). So if a student got A A A B B C C C C (with A=1, B=2, C=3) their average grade was B. This we view as the general Prior Attainment of the student.

We then make a table of average GCSEs and what they got in their English A Level.

So in this case, if your average GCSE was a B there's a 50% chance you'd get a B at English A Level. This is called a Prediction Matrix.

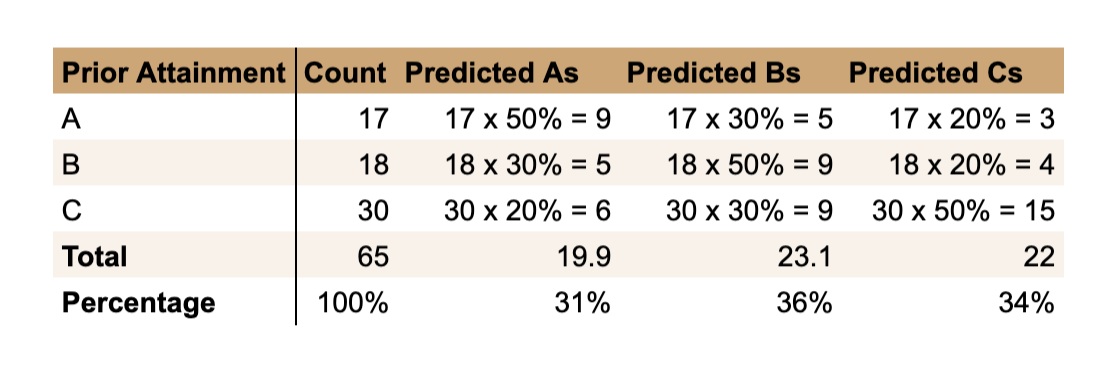

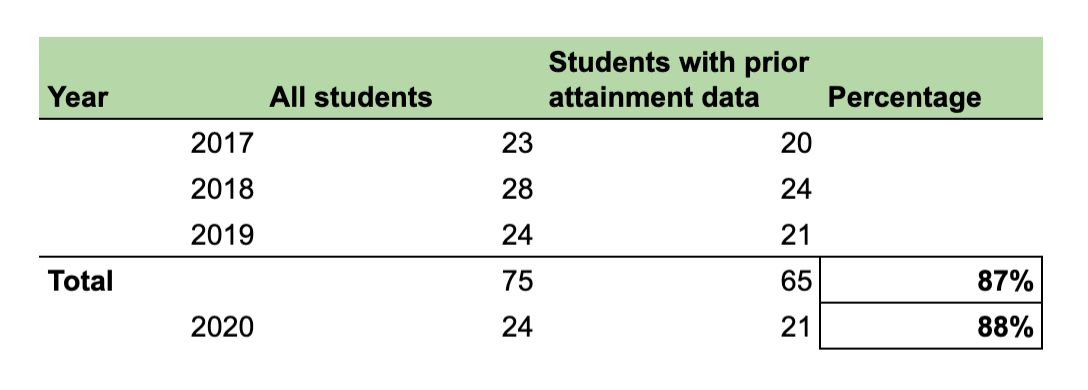

Don't forget, we're looking at national data here. What comes next is applying that to Cova Academy's historical cohorts. For the 75 students, we have prior attainment data for 65:

The other 10? We don't know what they got at GCSE. Either the data is bad, or they didn't do GCSEs, or they immigrated, or something else.

This grade distribution applied to our 24 students looks like this:

AAAAAAABBBBBBBBBCCCCCCCC

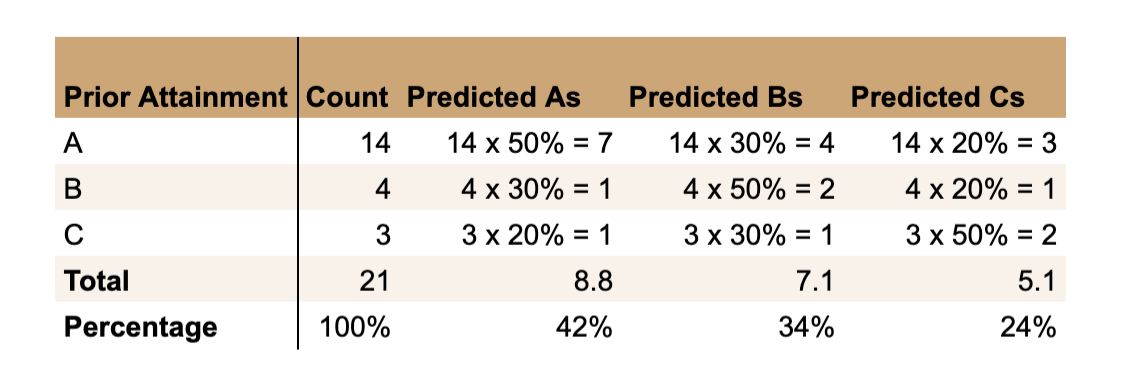

Grade Distribution Based on Students Like Cova's 2020 Cohort

The idea here is that to work out what the sort of students of the ability Cova has got this year typically get.

To do this, we simply apply the same prediction matrix as before to the current students' prior attainment:

Again, 3 we don't have data for.

This grade distribution applied to our 24 students looks like this:

AAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBBCCCCCC

So we now have 3 distinct distributions.

The next task is to mix them together somehow.

Step 2: Determine The Final Distribution

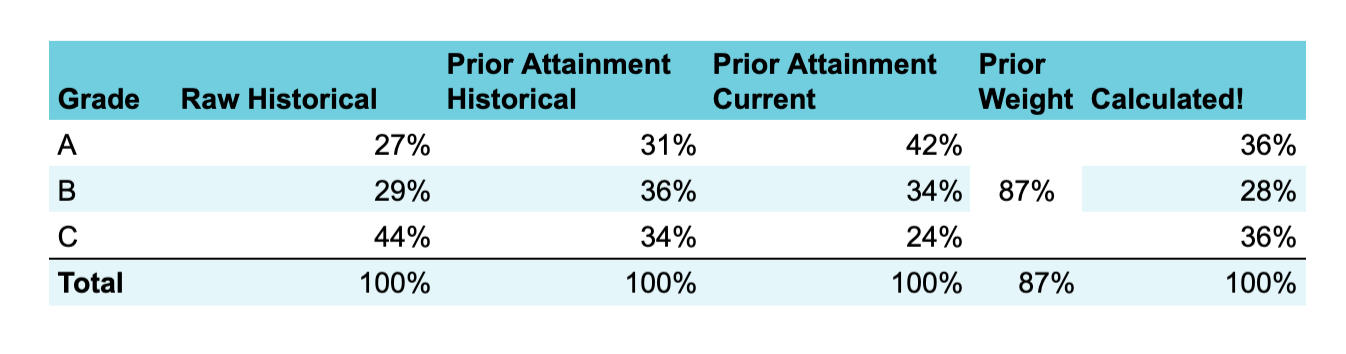

We mix these together based on how good the prior attainment data is. If a school hasn't got very much prior attainment data for either the current cohort or previous ones, we just ignore it and use the raw historical data. If it's all perfect, we use just the prior attainment and ignore the raw historical data.

In most cases, it's a mix. We work out the % of both historical and current students we have prior attainment data for:

And take the minimum of the two — in this 87%.

So our prior attainment data is pretty good, which means we weight it pretty highly. We do this by looking at how much better the current prior attainment is than the historical prior attainment, and then adjusting the historical grade distribution by that much.

To put this in crude terms, if the school has historically got classes that average at a C-grade, and this year we have a class that averaged at a B-grade, we take the historical performance of the school and adjust it upwards this year.

Let's see how it plays out:

So our grade distribution is now:

AAAAAAAAABBBBBBCCCCCCCCC

9 As, 6 Bs, 9 Cs. This is the 'bag of grades' a school is now assigned to give to their students. For Cova Academy, this is a better than average result, due to the cohort having done better at GCSE level.

But how are these assigned to students?

Step 3: Student Ranking

Ofqual asked Cova Academy's teachers for two pieces of information:

Predicted grades for each English student (CAG - Centre Assigned Grades)

A ranking of all students by performance in English (Rank Order)

Teachers got together and discussed all this, some schools moderated very carefully to make sure these were reasonable — others probably didn't. Ofqual couldn't provide detailed instruction because some schools would have been so badly affected by COVID19 that they couldn't have done it.

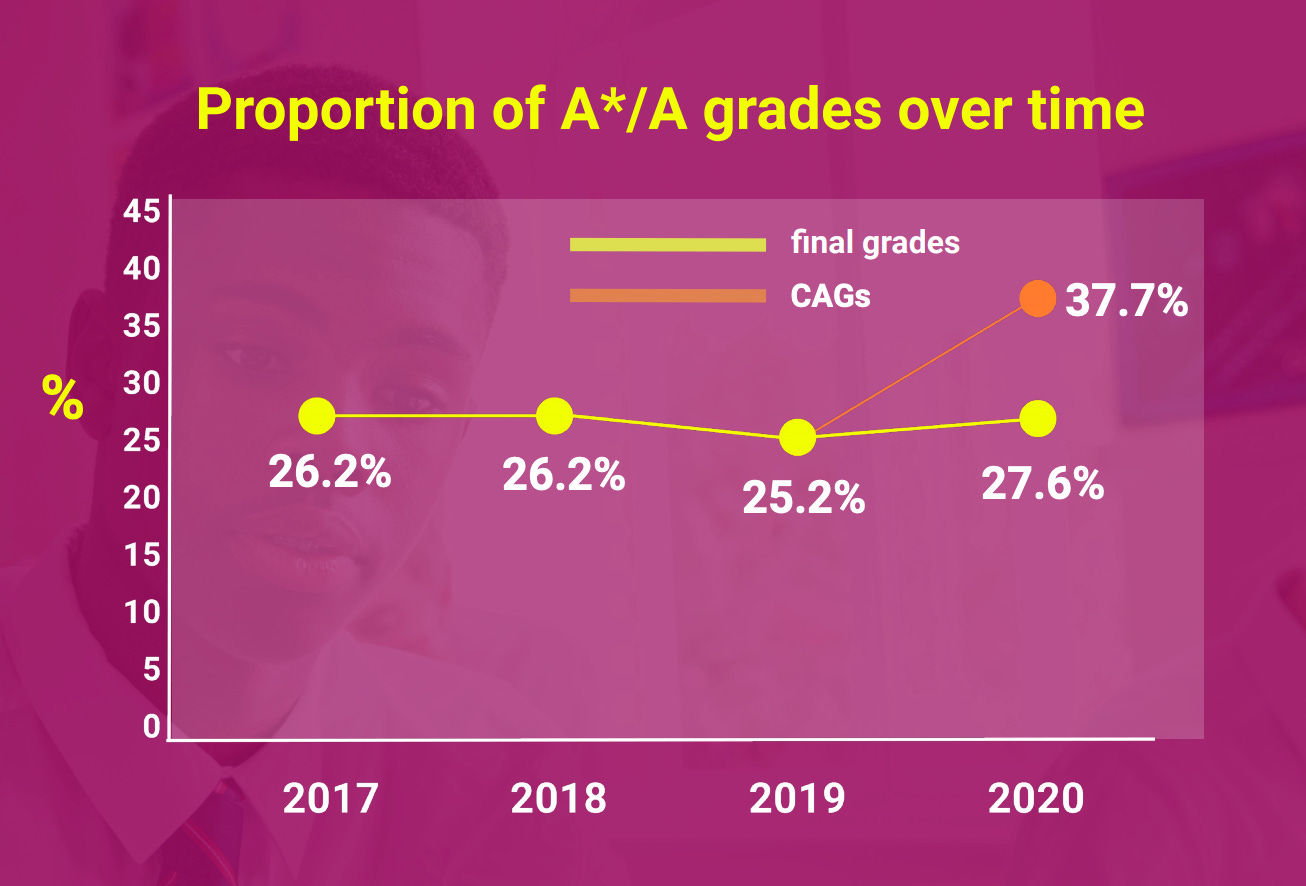

The thinking behind this is that teachers do know quite a lot about students and so can make reasonable guesses about how things will turn out. However, not only are teachers very optimistic about student performance:

And some studies indicate that teachers are biased in predictable ways for and against certain groups. Science teachers grade work higher if they believe it has been written by boys, and teachers in general tend to stick close to prior attainment. Here is a response from the consultation on Ofqual's plans:

An over-reliance on predicted grades will penalise BAME and disadvantaged students that are routinely under-predicted. A study by the UCL Institute of Education found that just 16% of applicants achieved the A-level grade points that they were predicted to achieve, based on their best three A-levels. Furthermore, research by the then-Department for Business, Innovation and Skills found that black students were most likely to have their grades underpredicted, and overall only 39% of their predicted grades were accurate, while their white counterparts had the highest, at 53%. The UCL study found that high ability disadvantaged students are particularly likely to have their grades under-predicted, and, once controlled for achievement, pupils from state schools are less likely to be over-predicted than those in independent and grammar schools. The reasons behind this pattern of predictions are complex, but one is likely to be persistent unconscious bias in the classroom.

Ofqual ultimately decided to review these biases on a systemic level (more on that later) and proceed with their plans.

Another challenge of this approach is that each school has to rank all of their students in a given subject. Cova Academy has 24 students in 3 classes of 8 — the teachers will be able to rank well within their classes, but how will they decide the full list of 24? They will have to discuss a lot to align amongst each other, and even then it will be tough. In larger schools this is even more of a problem.

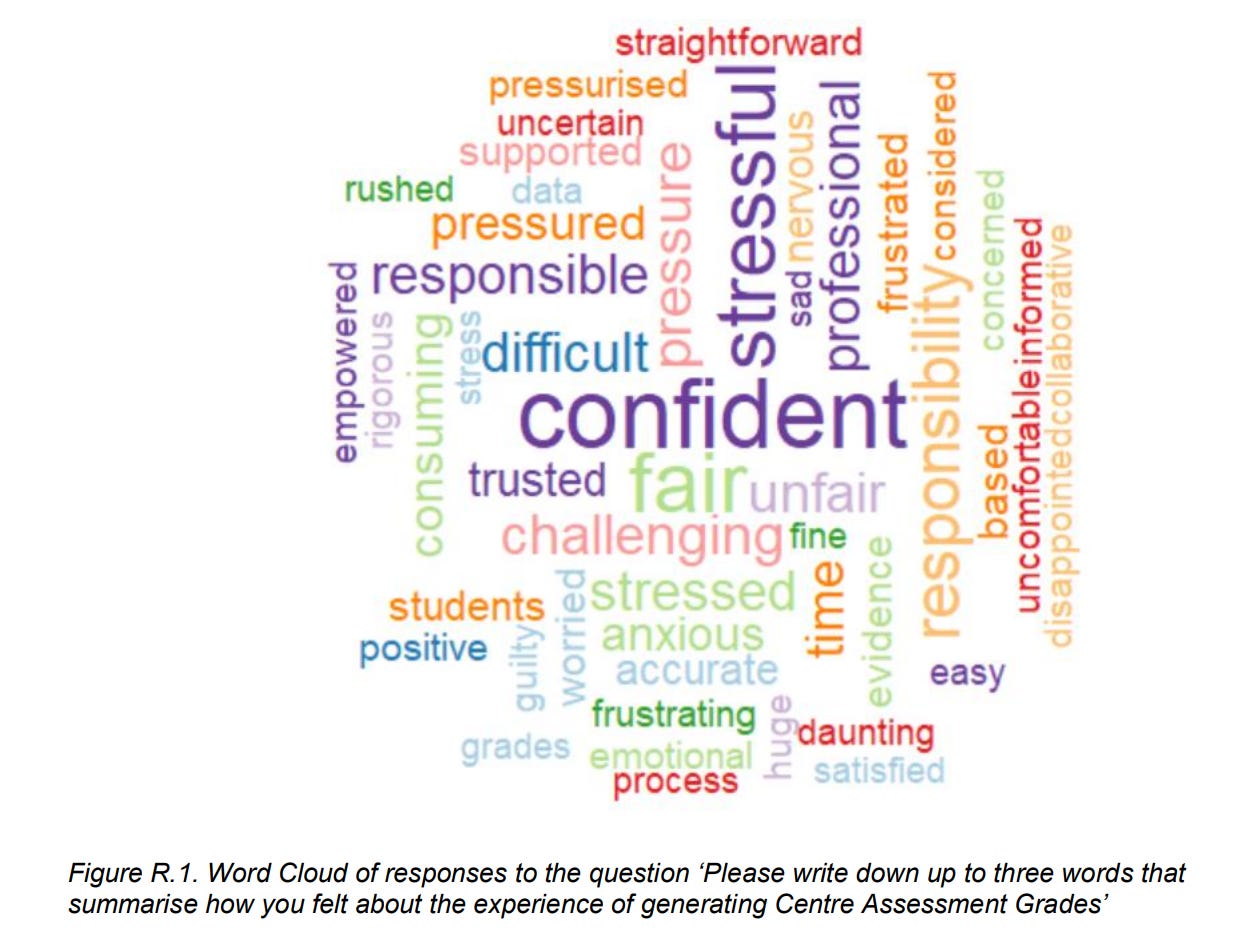

As a side note, here's a word cloud of teacher's reports on going through this process:

Reassuring huh?

In any case, using this approach Cova Academy came up with their rank order list of their 24 maths students and sent it off to Ofqual. Ofqual then just assigns them in order: the top 9 get As, the next 6 get Bs, the last 9 get Cs.

And that's essentially it for Cova Academy! There's a bit more fiddling around the edges to get the grade boundaries right and account for borderline cases, but that's the simplified(!) version.

What about small classes?

If your number of maths students is under 5, the above process is almost entirely useless as there is 'little statistical regularity'. So they just award the grades the teacher thought you'd get (CAGs).

If your class is between 5-15, they gradually phase between the CAGs and the model. If you have 6 students it's CAGs adjusted a little to include the model. If you have 14 students it's the model adjusted a little to include the CAGs.

This is almost entirely the reason why private schools have done better. A lot of independent schools have smaller numbers of students per subject. So they rely on the CAGs more, and the CAGs are overly optimistic, so they come out better. Ironically, I suspect this isn't Eton as it's got too many students — if you're looking for unfair advantages, look at small private schools.

What if you're really good at French?

Let's say your first language is French and you thought you'd be smart and get an A Level in it. You're not super academic, but this one should be a sure thing right? Sorry, not now!

If your prior attainment generally is average (your being really good at French doesn't mean you're great at school generally, you're just good at French) and your school doesn't have a lot of native French speakers (because it's in England) you're going to end up with a calculated grade that is average for your school.

What if you're really good at Russian?

Let's say your first language is Russian, and you end up in a small class of Russian enthusiasts at school. Your class is small, so your CAGs get weighted highly, and you're great at Russian so they're high. You get a great grade! Good news.

What if your school is having a tough time, had some bad GCSEs, but you've turned it around and fought against the odds to do great work at A Level?

Your brilliance will not be reflected in your calculated grades at all.

Does this system bias against, for example, black learners?

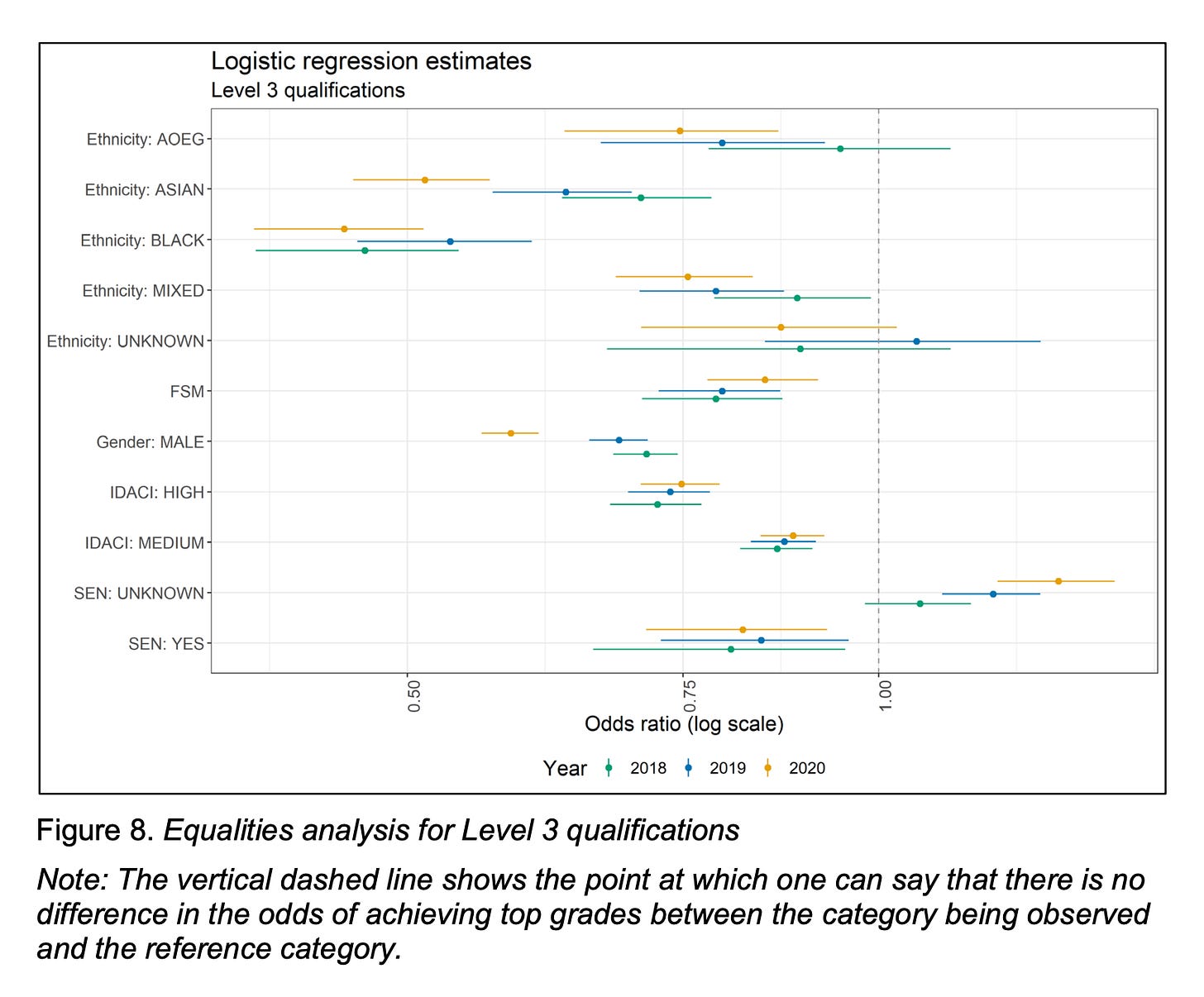

Let's take a look at this graph:

(Source)

What this shows is the odds of achieving the highest grades for different groups compared to reference groups (for ethnicity it's white people, for gender it's girls, for Income Deprivation (IDACI) it's people who aren't affected much by income deprivation). The dot is the estimate, the line is the range of values it could plausibly be.

The Odds Ratio for black learners is 0.5. That means for every 10 white learners who achieve the top grades, 5 black learners do.

You can see that the calculated grades are roughly in line with the results from previous years, except for boys and Asian leaners (the analysis is vague on why this might be, though notes that these are relatively small differences and there's no indication of whether the cause is a genuine difference in performance or due to their model). For the above process, it's a remarkably 'good' result that the distribution falls out.

However, what should strike us when you look at this graph is that the 'normal' results are horrifically bad.

What are we doing here?

This outcome is reminiscent of so many scenarios where a large organisation has decided to create an algorithm to predict or perform certain work. They get a bunch of input data, inject it into their algorithm — and then are seemingly surprised when the outcome reflects the bias that has gone into it.

What are the ethics of reproducing this system? Here's a rather strong line from the consultation:

[I] disagree with the underlying principles. These aims are about preserving the status quo in a situation which has no historic parallel. This is morally indefensible for the students affected by this.

Ofqual did put a small amount of thought into ethics here. The principles were:

To provide students with the grades that they would most likely have achieved had they been able to complete their assessments in summer 2020

To apply a common standardisation approach, within and across subjects, for as many students as possible

To protect, so far as is possible, all students from being systematically advantaged or disadvantaged, notwithstanding their socio-economic background or whether they have a protected characteristic

To be deliverable by exam boards in a consistent and timely way that they can quality assure and can be overseen effectively by Ofqual

To use a method that is transparent and easy to explain, wherever possible, to encourage engagement and build confidence

They have also made an interesting decision re: qualifications. Not all grades are being calculated. Grades that confer professional respect or confidence (say, to an electrician) have simply been delayed as it would not be safe for society to label someone an electrician without having... learned to be an electrician.

So it is only grades to do with progression that have been calculated. And why? So people can get on with their lives. The slightly uncanny conclusion is that these grades are not designed to reflect learning, but to efficiently allocate society's resources, in the form of higher education places, to those with aptitude who are able and willing to work hard consistently. Effectively, the learning is not the point.

(There is an exception for English and Maths GCSEs here, which are the only qualifications used in real life to determine competence.)

What are the consequences?

Taking an 'educational realism' approach, what have we done?

We have allocated university places based on broad demographics rather than individual attainment, in this way preserving the general pattern while distorting many individual results.

We have made a lot of people very upset at these individual injustices.

What happens next?

Well everyone hates it.

It's a big mess. In England, the government is currently working with new proposal that the higher of the calculated grade and a 'mock exam'(?) can be assigned as the given grade —unless the CAG is lower than the mock grade, in which case they get the CAG. And then they can take an exam in Autumn if they want to boost it up.

There are some problems with this:

CAGs don't represent the grades students would probably have gotten, and plenty will be biased.

Some schools were likely very generous and free with CAGs, some moderated them very carefully. Is this a fair distribution? Probably not.

Mock exams aren't standardised at all, could be harder or easier, are often used just to scare students into working harder.

The meaning of qualifications in general are suspect, meaning grades will likely be 'worth less' and emphasising any bias in the CAGs.

University places have already been allocated anyway, so later changes will have few practical consequences until next year.

Next year's students will now have fewer places available to them, and will likely be marked — if not 'harsher' than this year, certainly fairer. They will essentially have to perform substantially better than they otherwise would have in order to get a place.

It’s worth noting that Ofqual issued and then a few hours later retracted the new plan pending review — so we’ll see how that pans out. One thing is for certain: all of this is going to take a long time to undo.

Which takes me back to my fish experience right at the beginning. The education system is unfair. The reason people believe in it is because it has the veneer of fairness, that in some way it is under your control.

These results are not particularly abnormal — some students have worse days than expected, don't get the grades they could have. Some schools have bad years or break a rising streak. Usually these are not news because people generally assume they have agency.

In Brechtian theatre there is the idea of alienation — in which the audience should not be immersed in the drama but in fact regularly reminded of the artificialness of what they are experiencing. By demonstrating that educational outcomes can be predicted to a degree of brutal societal accuracy, by demonstrating that our government is willing to undertake a project to do so and that so many went along with it, they have created a similar effect.

Many are being reminded now of what they already knew but ignored, that this is not merely unfair but unjust, that their success is arbitrarily decided, and that their lives hang in the balance.

It will have echoes, and I doubt this will be the last such event COVID triggers.

K

[Amended to correct some wording around the current working plan.]

So glad I understand all of this now!